Many kinds of music derived from African American traditions come together under the umbrella of “jazz.” Over several decades, these musical styles accompanied the large waves of migration from the southern United States to cities like Chicago and New York. In the 1920s, jazz reached a much broader audience thanks to the record industry and radio broadcasting. For Mondrian, there were two key elements of jazz: the fact that it was syncopated (the musical accent can occur anywhere in the measure) and polyrhythmic (different rhythms are produced simultaneously in the music, or between the music and the dance steps).

Mondrian’s studios—first in Paris and later in New York—were work spaces in which music from his collection of 78 rpm records (which was the main sound recording format of the time) was constantly playing on his gramophone. In Paris, despite his austere lifestyle, he had a considerable music library: sixty-seven records featuring styles such as swing, blues, and the most popular dance tunes of the time. Mondrian’s personal music collection included singers and musicians such as Duke Ellington, Billy Cotton, Paul Whiteman, Frankie Trumbauer, Bix Beiderbecke, Red Nichols, and, in the 1930s, Cab Calloway and Big Joe Turner.

Piet Mondrian and Gwen Lux in the studio of Mondrian, Paris, 1934. Photo: Eugene J. Lux.

RKD-Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis

(Collectie Archivalia), The Hague

Piet Mondrian and Gwen Lux in the studio of Mondrian, Paris, 1934. Photo: Eugene J. Lux.

RKD-Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis

(Collectie Archivalia), The Hague

The phonograph, sound recordings, and the music played on the radio allowed Mondrian to listen in a radically different way. By no means mere simplifications of the live concert experience, these technologies enabled an attentive, unique, revolutionary kind of listening: Mondrian was fascinated by sound recording. Composer and music critic Paul Sanders kept a record of his conversations with Mondrian, who once talked to him about the gramophone: “No, Paul, believe me, the gramophone and radio will bring about a revolution. They will put us in the position for the first time of being able to listen in a concentrated way, undisturbed by other listeners who cough, or tap out the rhythm with their feet or distract us in other ways. You will be able to sit listening in your room with as much attention as you might read a book, or look at a painting or print on the wall.”

For Mondrian, jazz was not just an ear-pleasing music to dance to: while listening and dancing, he tried to identify the underlying structure of the jazz of his time, the kind that is not subsumed to the constant repetition of beats in musical meter. Mondrian’s passion for dance would appear to contrast strongly with the austere and introverted figure we see in photographs of him. But unlike other artists of his time such as Henri Matisse and Stuart Davis, his interest in jazz music and dance was based on the abstract formal qualities of the rhythm. When he discovered the dancer Josephine Baker performing in the Revue nègre in Paris in 1925, with an excellent jazz band and her polyrhythmic dance style, she immediately became his favorite “modern dance” performer.

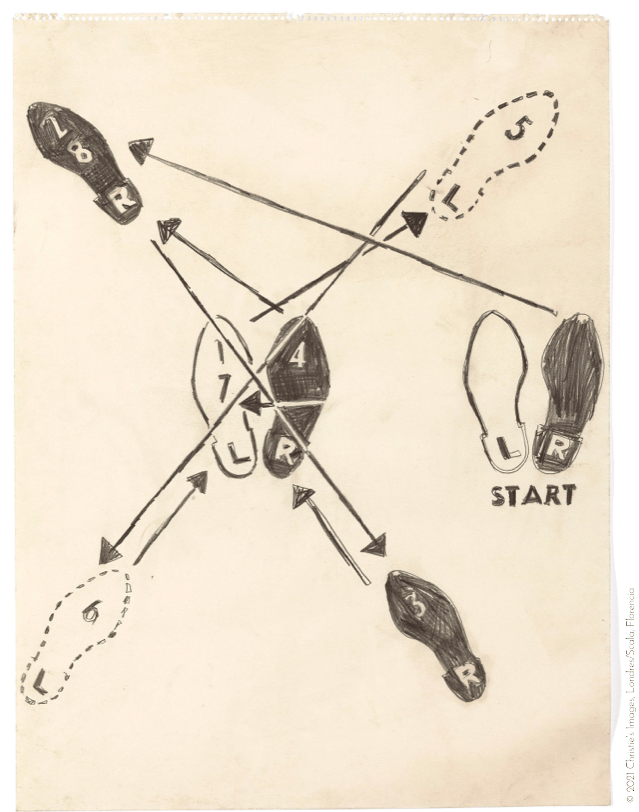

Andy Warhol, Dance Diagram, 1962.

Christie’s Images Ltd., London

Andy Warhol, Dance Diagram, 1962.

Christie’s Images Ltd., London

According to some of his closest friends, in Paris Mondrian promptly signed up to what we would now generically call “ballroom dancing” classes: foxtrot, tango, swing, Charleston, and so on. He knew the basic steps of all the modern styles, and indeed, theorists have speculated about how the patterns of those dance steps influenced some of his paintings. Mondrian apparently held himself very upright when he danced, moving along a straight line with unusually fast steps. However, it was while dancing to jazz, keeping perfect time, that he tried to devise more inventive steps, displaced from the beat. He was a great dancer in his own way—but not a very good dance partner. As Michel Seuphor remembers, it was too complicated to follow his steps. Seuphor also describes Mondrian’s constant visits to Parisian cafés and clubs such as La Cigogne, on the boulevard Saint-Germain, and Le Boeuf sur le Toit, where the Group of Six (whose members included Darius Milhaud and Francis Poulenc) often gathered.

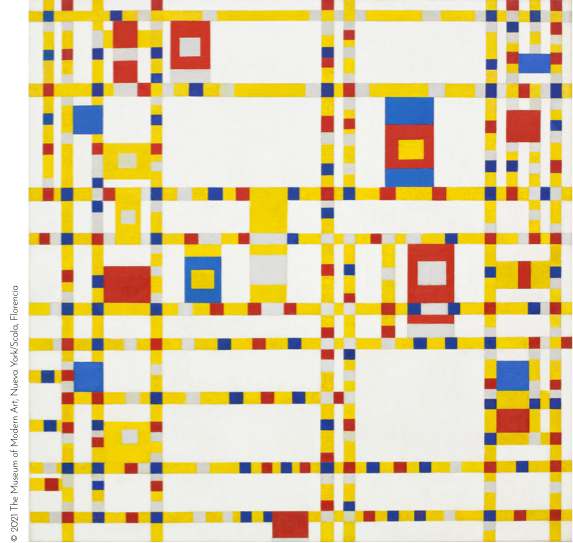

Boogie-woogie emerged in the early twentieth century among African American pianists in the rural southern United States. It later reached the cities, and the first recordings were made in the 1920s. Although the style had been around for a while, the term first appeared in the title and lyrics of the 1928 recording “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie,” by pianist Clarence “Pinetop” Smith. Harry Holtzman played Mondrian a boogie-woogie record on his first or second night in New York in 1940. Mondrian responded very enthusiastically. According to Holtzman, Mondrian kept three boogie-woogie records and six compilation albums in his studio.

Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie-Woogie, 1942—1943.

The Museum of Modern Art, Nueva York

Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie-Woogie, 1942—43.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

While painting Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942—43), Mondrian constantly listened to boogie-woogie records such as “Roll’em Pete,” by pianist Pete Johnson with trumpeter Oran “Hot Lips” Page, and “Boo-Woo,” also by Johnson, with Harry James on trumpet. With his friend Harry Holtzman, Mondrian also frequented Harlem and downtown boogie-woogie clubs such as Café Society to listen to the best boogie-woogie pianists (Jim Yancey, Albert Ammons, and Meade Lux Lewis). Mondrian used the musical structure of boogie-woogie as a direct model for his painting. Indeed, when Broadway Boogie-Woogie was first exhibited in 1943, MoMA director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. already noticed the link between the painting’s horizontal lines and the left hand of a boogie-woogie pianist (which repeats the chords of the ostinato bass), and between the asymmetrical rectangles and the syncopated rhythms of the pianist’s right hand.