Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, s. f. RKD—Nederlands Instituut

voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Archivalia), The Hague

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, s. f. RKD—Nederlands Instituut

voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Archivalia),The Hague

Theosophy is a kind of esoteric spiritualism based on Eastern religious doctrines (Hinduism and Tibetan Buddhism); the mystical traditions of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece; and the exploration of human psychophysical dynamics. Theosophists sought to bridge the gap between spirituality and techno-scientific progress. Mondrian joined the Theosophical Society in 1909 and read Blavatsky and Rudolf Steiner, among others. In a 1918 letter to his friend and fellow theosophist Theo van Doesburg, he wrote, “I got everything from Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine.” Mondrian considered his Neoplasticism to be the art of the future, a “true” example of theosophical art.

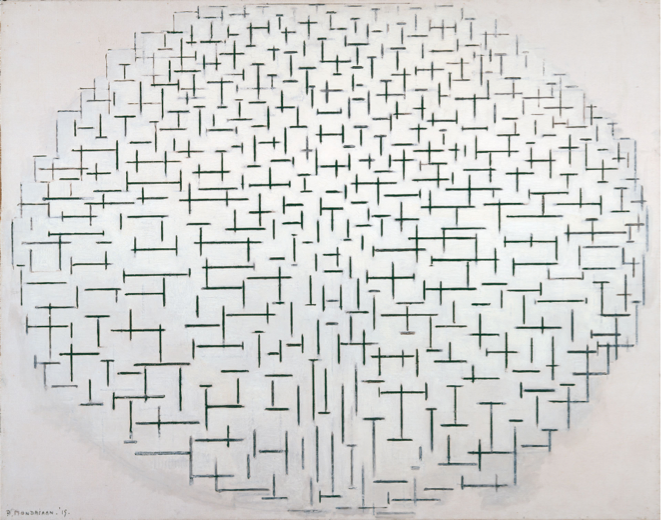

Piet Mondrian, Compositie 10 in zwart wit (Pier and Ocean)

(Composition 10 in Black and White [Pier and Ocean]), 1915

Kröller-Müller Museum Collection, Otterlo (Netherlands)

Mondrian had first-hand knowledge of the changes that were taking place in Western music in the early decades of the twentieth century. His theory of musical Neoplasticism and his concept of visual rhythm were strongly influenced by his conversations and the exchange of ideas with Dutch composer and theosophist Jakob van Domselaer. In turn, Mondrian’s paintings directly inspired one of Domselaer’s major scores, the piano suite Proeven van Stijlkunst (Experiments in Artistic Style, 1913–16). It is a work that shares many of Mondrian’s aesthetic ideas: the elimination of melody, an emphasis on harmonic structure over melodic development (expression between horizontal progression and static verticality), the emancipation of rhythm, and the quest for static rhythm in the paintings of his middle period (before he started using double lines in the 1930s). The first Proeven van Stijlkunst was very highly regarded by Mondrian.

At the end of World War I, Mondrian met Amsterdam-born composer and pianist Daniël Ruyneman and started to share with him many of his artistic concerns. Ruyneman sought in his compositions to simplify materials and to dissolve melody in order to stop the flow of sound. His music featured a contrasting harmonic balance, constant changes, and unusual sound combinations. All of these factors were later included by Mondrian in his theoretical texts on Neoplastic music. Both Mondrian and Ruyneman wrote about the need to invent new instruments, and Ruyneman implemented some of his experimental musical instrument designs.

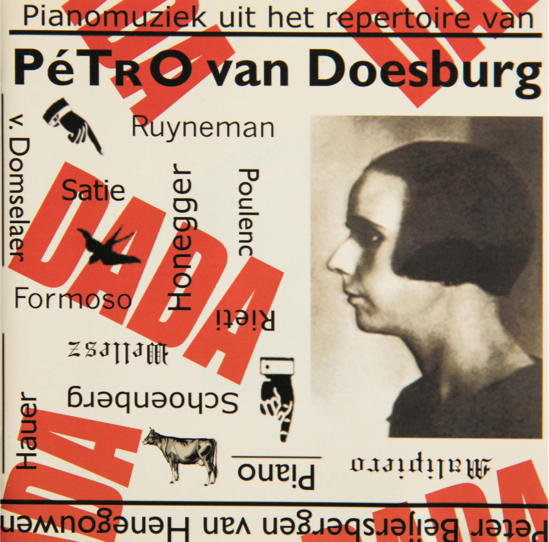

Mondrian’s friendship with the pianist, dancer, and artist Nelly van Moorsel also played an important role in shaping his aesthetic views. They met when van Moorsel accompanied her partner, the artist Theo van Doesburg, to Mondrian’s studio in 1921. Under the stage name Pétro van Doesburg, Nelly gave numerous recitals and participated in some of the famous “Dada evenings.” Her concert programs include piano works by musicians associated with the De Stijl movement, compositions by the Group of Six, and pieces by composers as diverse as Arnold Schönberg, Erik Satie, Gian Francesco Malipiero, and Vittorio Rieti. After publishing his article on the Italian noise musicians, comparing notes with Nelly helped Mondrian refine a notion with far-reaching consequences for the formulation of Neoplastic art: the duality between sound and nonsound. According to Mondrian, the opposite of sound (of color) is nonsound (noncolor), which consists of noise (an abrupt interruption or caesura within the sound itself). As Mondrian explained, silence is dangerous, because it allows listeners to fill up the empty space with their own individuality, thus moving away from universal expression.

Mondrian met Charmion von Wiegand, an artist and scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, in New York in 1941, leading to an enduring friendship and artistic relationship. By the time of his arrival in the United States, Mondrian was no longer a member of the Theosophical Society, but some years later von Wiegand said that he never rejected the practices and knowledge acquired during his theosophical education in the 1920s. As other writers have pointed out, although Mondrian adapted theosophical doctrine to his own personal criteria, the cultural and personal circles in which he carried out his work included many members of the Theosophical Society and other mystical traditions. Von Wiegand herself came from a family of theosophists and later went on to become a student of Armenian mystic, spiritual teacher, and composer George I. Gurdjieff.

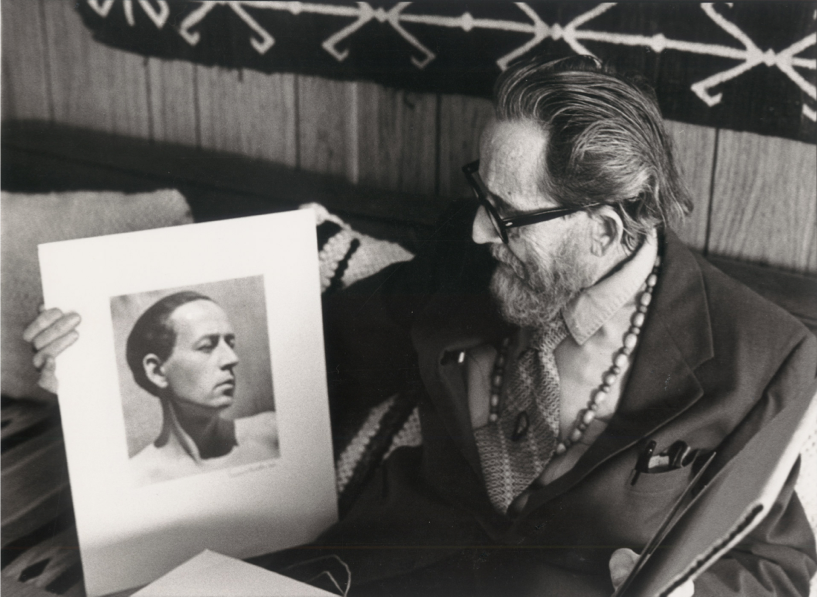

Dane Rudhyar looking at an Edward Weston portrait of himself in the 1920s. Photo: Betty Freeman. Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives, Los Angeles

Dane Rudhyar looking at an Edward Weston portrait of himself in the 1920s. Photo: Betty Freeman. Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives, Los Angeles

Of the composers who revolutionized music in the United States, the so-called ultramoderns (Carl Ruggles, Henry Cowell, and Ruth Crawford) established links between dissonance and theosophical spirituality. Composer and philosopher Dane Rudhyar was a key figure, although he is seldom mentioned. Mondrian and Rudhyar did not actually meet either in France or the United States, but there were some commonalities between them. All the artists and composers directly or indirectly linked to theosophy shared the desire to find a deeper, unexplored, or—to borrow a term commonly used by these artists—more “universal” form of creative expression. Rudhyar believed the role of the new composer would be more akin to that of a magician or a medium: someone who makes it possible to connect to deeper psychic states (which would be inaccessible without the appropriate training). Rudhyar’s music unfolded through a dynamic momentum, with clusters of not necessarily tonal sounds, and a notion of rhythm that was more like a particular way of flowing than a series of precise metronomic calculations. Mondrian and Rudhyar shared an aesthetic interest in the search for structural rhythm, like that which the sea expresses in the flow of the waves.

Unknown photographer, L’intonarumori di Russolo con

Russolo e Piatti (Russolo and Piatti with

Russolo’s Intonarumori), ca. 1913. Private collection

Unknown photographer, L’intonarumori di Russolo con

Russolo e Piatti (Russolo and Piatti with

Russolo’s Intonarumori), ca. 1913. Private collection

In the 1920s, Mondrian consolidated his theory of Neoplastic art thanks mainly to two key discoveries: jazz music, with its syncopated rhythm, abrupt melodic breaks, and closeness to a more “universal” rhythm, and Futurism, which was essential in formulating the duality of color (sound) and noncolor (nonsound). In 1921, Mondrian attended a concert by the Italian Futurists’ Bruiteurs at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, featuring Luigi Russolo’s then already famous intonarumori (noise machines) as well as more conventional orchestral instruments. Although the contrasting sounds of the new Futurist instruments made an impact on Mondrian, he did not find the musical realization altogether satisfying: it remained too constrained by melodic development (by natural subjectivity) and by the sequential repetition of the rhythm (which was contrary to the quest for Neoplastic rhythm). Although there are today no sound recordings of these instruments, and none of them have been preserved, we can get an idea of their sound through a version produced by Daniele Lombardi in 1978, using the intonarumori reconstructed for a Luigi Russolo retrospective at the 1977 Venice Biennale. This recording includes a thirty-second fragment of the piece Risveglio di una città (Awakening of a City) and five excerpts featuring each of the following instruments: crepitatore, ululatore, gorgogliatore, ronzatore, and arco enarmonico.