Thelonious Monk at Milton’s Playhouse, New York, 1947

Photo: William P. Gottlieb. Courtesy of the William P. Gottlieb Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

Thelonious Monk: When Thelonious Monk was interviewed by Harry Holtzman in 1948, he claimed that he was by no means satisfied with his recordings. Indeed, if there is one jazz musician known for meticulous rigor in the 1940s and 1950s, it is Monk. His technically unorthodox style was remarkable for its modification of familiar material, rhythmic displacement, extreme dissonance, the use of “crushed notes” (which must have enthused Mondrian), and the unexpected rubatos. It was Holtzman who took Mondrian to Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem so the two could meet (Monk’s first album, with Charlie Christian’s group, was recorded live at Minton’s Playhouse and captures the live ambience of the clubs of the time: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZVu0cR0r6vA). Nelly van Doesburg recounted how in 1947, after Mondrian’s death, Monk would spend hours at the piano rehearsing the precision and intensity of each keystroke and the moment at which it should occur. Monk compared this exploration to the precision with which Mondrian placed the lines and colors on the canvas. One of Monk’s early compositions, “Evidence,” recorded for the Blue Note label on June 2, 1948, is paradigmatic of his astonishing style in this early period.

Morton Feldman: “I learned more from painters than I have from composers,” Morton Feldman wrote, summing up the influence of the visual arts on his compositions and musical aesthetics. Artists such as Philip Guston, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Piet Mondrian significantly altered his musical thinking and compositional practice. Echoing the Coptic textiles and Persian rugs that Feldman loved, music and the visual arts are woven and knotted together in his musical aesthetic. The young Feldman never met Mondrian in person, although he was able to see his late jazz-inspired paintings in New York. However, Feldman was fascinated by the paintings from his middle period, and more curiously still, by those from his Domburg period, when Mondrian’s commitment to abstraction began. In these works, nature and the sea are a confirmation of constant renewal as a regulating principle of the universe. These Mondrian paintings were extremely important to Feldman. They strongly foreshadow his compositions and invoke key notions of his musical thought, such as “asymmetrical rhythm.” Feldman’s interest in Mondrian’s paintings does not just come through, transformed, in his compositional process, but also in his representations of it during his “graphic notation” period (1950–67).

Louis Andriessen: Dutch composer Louis Andriessen structures his works using techniques that are very similar to American musical minimalism. Exploring various aspects of the “spirit-matter” relationship, Andriessen became fascinated by Mondrian’s work, especially by the coexistence of extreme rigor in his abstract paintings and an intense love of dancing. The third part of Andriessen’s De Materie (Matter, 1984–88) is a tribute to Mondrian’s aesthetic and work, specifically the painting Compositie: No. III, Met Rood, Geel, en Blauw (Composition III with Red, Yellow and Blue, 1927), now in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Andriessen determined the rhythmic structure of the musical composition (the number of “black notes”) based on the dimensions of the painting. Starting with the primary colors, straight black lines, and rectangular shapes that appear on the canvas, he divided the orchestra into five groups and assigned elements of the painting to each group. Although Mondrian was not familiar with boogie-woogie at the time the painting was created, Andriessen linked the black lines to the ostinato of this musical style, thereby also including Mondrian’s last period in the composition as well.

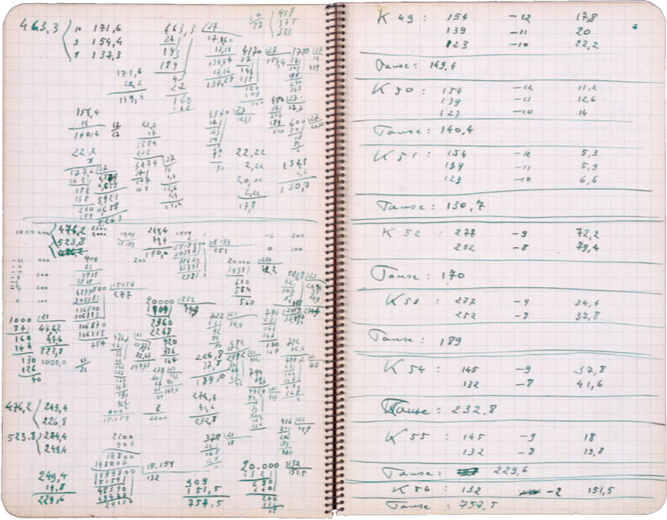

Double page of Karel Goeyvaerts’s notebook no. 5.

Universiteitsarchief KU Leuven, Archief Karel Goeyvaerts, Leuven

Serialism and electronic music: During the rise of musical serialism in the second half of the twentieth century, musicians regularly mentioned certain visual artists and architects. Mondrian’s aesthetic views in general, and his principles of abstract art in particular, stood out among these extra-musical influences. Belgian composer Karel Goeyvaerts was a student of Darius Milhaud and Olivier Messiaen, and attended the Darmstadt New Music Summer School in 1951. Goeyvaerts wrote the electronic composition Nummer 5 met zuivere tonen (Number 5 with Pure Tones) at the WDR Studio for Electronic Music in 1953, with the assistance of Karlheinz Stockhausen. The “pure tones” of the title is a reference to the use of sine waves. The use of these waves without harmonics (which are fundamental in any account of a great deal of experimental music), the elimination of expressive attacks, and the rigorous ordering of the material into symmetrical and asymmetrical series are astonishingly close to several fragments of Mondrian’s own texts on musical theory, such as the passage in which he writes, “To neutralize undulation and fusion—thus the domination of the individual—other instruments are inevitable. If we are to abstract sound, the instruments must first produce sounds as constant as possible in wavelength and number of vibrations. Then they must be so constructed that all vibration will stop when the sound is suddenly broken off.” (“De ‘Bruiteurs Futuristes Italiens’ en ‘Het’ nieuwe in de muziek,” De Stijl 4, nos. 8 and 9 [1921]; English from The New Art—The New Life: The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian [Boston: G. K. Hall, 1986], 153.)

Iannis Xenakis: In 1994, Iannis Xenakis composed Ergma (Finished Work) for string quartet. The title is a direct reference to Mondrian’s abstract art, and the piece was composed by choosing some extremely simple technical elements in advance. In the 1990s, Xenakis explored different structural procedures that took him away from the characteristic stochastic processes of his best-known works. Thus in Ergma he simplified the choice of sound material: the performers almost constantly use two strings simultaneously, and only two intervals are used. During most of the work, the four string instruments are perfectly synchronized and proceed at a very slow tempo. The music unfolds through vertical groupings or conglomerations that invoke the placement of the pictorial elements in the paintings of Mondrian’s middle period: black lines and blocks of primary colors interacting to create patterns of continuous vibration, that is, a static rhythm.

Picnic in Space: In 1973, media theorist Marshall McLuhan made a film with Harley Parker distilling the key concepts of his thinking and his theory of culture. McLuhan’s voiceover starts by describing different types of space: acoustic space, the notion of space in ancient Greece and Rome, and various kinds of space put forward by the sciences and art. This first part of the film (from 3:21) includes images of Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie accompanied by a boogie-woogie piano soundtrack. Like Mondrian’s “acoustic painting,” which conjures up a post-Euclidean space different to three-dimensional space, McLuhan suggests that the acoustic, nonlinear space exemplified by this painting is distributed equally in the realms of the other senses, and that three-dimensional space is just one specific kind of space. The electronic music featured in the film was composed by Morton Subotnick, a member of the San Francisco Tape Music Center. Through the acoustic visual medium of film, McLuhan drew on Mondrian to reconstruct a kind of theory of sensory space.

Sándor Vály: Hungarian composer and sound artist Sándor Vály was born in Budapest in 1968. In 2009, he embarked on a project on Piet Mondrian’s painting and his views on music, in collaboration with pianist Éva Polgár, who was responsible for composing the scores and interpreting the piano part in the final works. The project came into being in various forms and media: a CD, concerts, texts, an exhibition, and several audiovisual works. Here we have selected the works related to Mondrian’s later paintings.

Mondrian Variations: Broadway Boogie-Woogie 1942–44 (2012): A deep knowledge of Mondrian’s work allowed Sándor Vály to establish a process through which to “musicalize” some of his paintings. The most complex decision was how to determine the pitch of the notes. Vály set up a relationship between a circle of primary colors and a musical circle of fifths. For the color gray, he turned to Mondrian’s musical theory on the relationship between unity and duality. The notions of “color/noncolor” and “sound/nonsound,” which are clearly set out in Mondrian’s theoretical writings, also appeared as part of the score. Vály then assigned the primary colors to the notes of the keyboard, and the nonsounds (the whites, grays, and blacks) to sounds outside of the musical scale (Mondrian called them “whirring” or “noises”). By preparing the piano (with a guitar pick) on the D strings, the color gray became a distorted note within the musical notation, placed—in confrontation— between the notes with precise pitch and timbre. At the same time, the note lengths correspond with the millimeter proportions of the placement of the colors in the painting Broadway Boogie-Woogie.

Broadway Boogie-Woogie concert at Pori Art Museum,

Pori (Finland), 2012

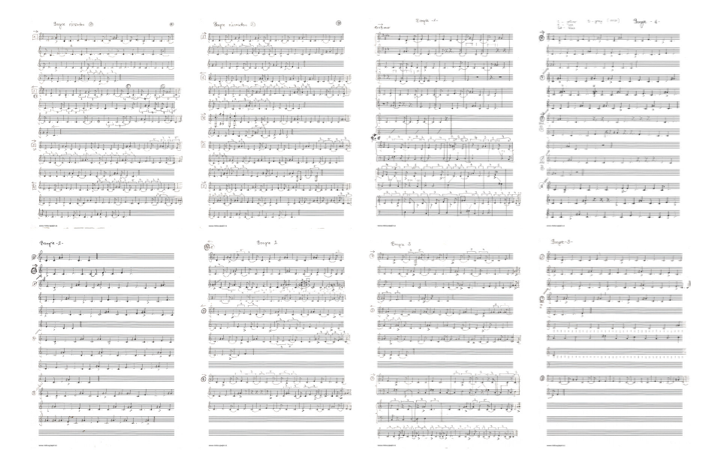

Mondrian Variations: Broadway Boogie-Woogie 1942–44, 2012

Sándor Vály, score for the Mondrian Variations: Broadway Boogie-

Woogie 1942-44, 2012

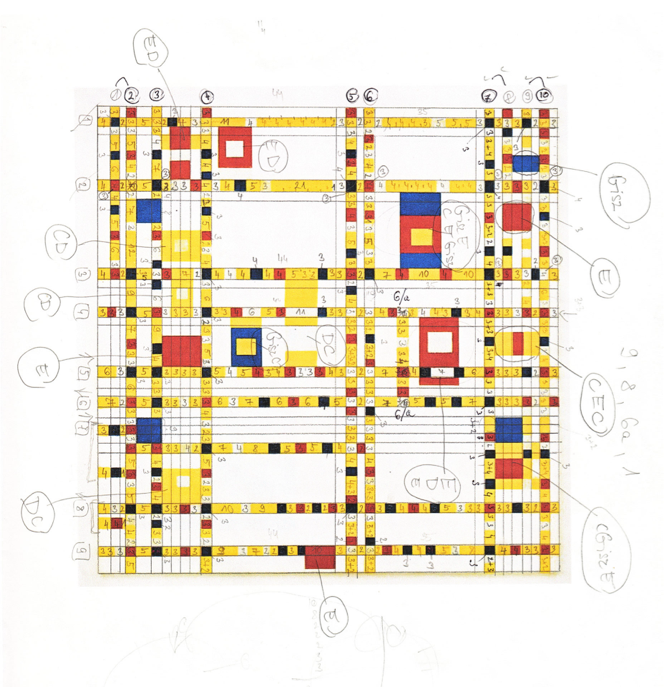

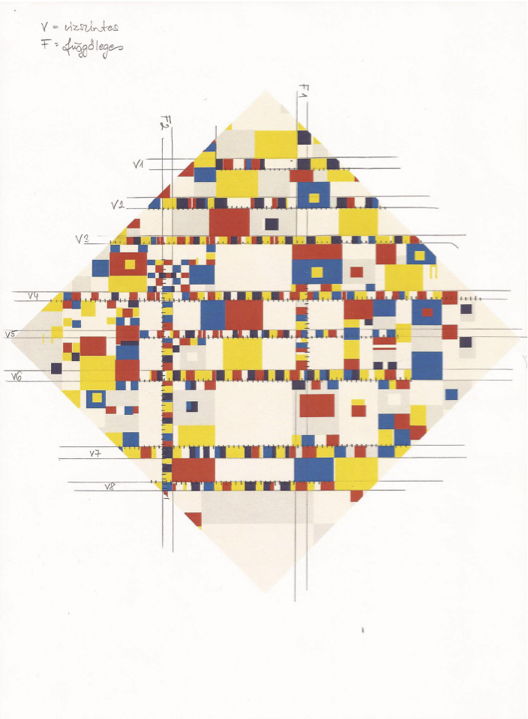

Sándor Vály, draft score for the Mondrian Variations: Victory Boogie-Woogie 1942–44, 2012

Sándor Vály, draft score for the Mondrian Variations:

Victory Boogie-Woogie 1942–44, 2012

Mondrian Variations: Victory Boogie-Woogie 1942–44 (2012): Mondrian’s unfinished Victory Boogie-Woogie was among the works analyzed and musicalized by Sándor Vály. By dividing the painting into color bands of different sizes, Vály began the structural work of transposing the visual register to sound. To do this, he borrowed some of the compositional strategies from Morton Feldman’s “graphic score” period (1950–67). The use of grids allowed him to extract key elements to complete the composition. Thus the rhythmic structure of the music arises from the position and distribution of the colors on the canvas. Art critic Hellmuth Christian Wolff suggested that the “V” (which appears in the title and in the alignment of Mondrian’s canvas) represents the victory sign of the allies in World War II. In Vály’s case, he uses music and sound strategies to show the hidden dark side of the word “victory”: the trail of suffering and atrocity when a war ends.